|

|

|

Wildcat History

Page Created

5/27/01;

Updated

3/21/04

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Part Two

HailToPurple.com

occasionally posted passages

from several texts giving anecdotal histories of the Wildcats.

What follows are

the collected passages originally posted weekly. The accounts are

given in the order that the events that they describe took place.

Again, these passages are not original to this site: the sources

are given before each quote.

1943:

Automatic Otto's Wild Season

1943:

Automatic Otto's Wild Season

This

section,

describing the 1943 season and the climax of Otto Graham's college

career,

is from The Tale of the Wildcats, a Centennial History of

Northwestern

University Athletics.

The

Wildcats

of '43 both started and finished in style, winding up the Conference

campaign

with five victories and one defeat, the loss being at the hands of

Michigan,

which, like Purdue, swept through the schedule undefeated.

Although

30 members of the '42 club were lost through graduation and to

the

armed forces, Northwestern's second wartime football club was a veteran

one. In addition to 14 lettermen, there

was

an impressive array of transfer students from other schools who were

enrolled

in the Navy's V-12 unit. Among them were several Minnesota

players,

Herman Frickey, Herb Hein, and Jerry Carle.

The

Wildcats

introduced themselves formally in a night game at Dyche Stadium and

accomplished

a 14-6 victory over Indiana, which presented a freshman named Bob

Hoerschemeyer

to scare the Wildcats until Graham's passes prevailed. Michigan

was

favored to win and did, but only because of another transfer from

Minnesota,

Bill Daley. The final score was 21 to 7, to which Daley

contributed

touchdown runs of 37 and 64 yards.

Graham's

passes

featured a 13 to 0 triumph over Great Lakes [Naval Base], and Otto the

Omnipotent also engineered a 13 to 0 beating of Ohio State, scoring one

touchdown and passing to Lynne McNutt for another. In the

Minnesota

game the former Gophers in the NU lineup received a real jolt when

their

old schoolmates scored in eight plays following the kickoff, but then

Graham

pitched a 50-yard scoring pass to Hein, Carle kicked the point, and the

Wildcats were on their way to a 42 to 6 decision. . . .

Graham

had a

field day at Madison in the course of a 41 to 0 brush with

Wisconsin.

Otto contributed three touchdowns and three extra points in the first

12

munutes, returned a punt 45 yards for a touchdown in the third period,

and tossed a fifth score to Wallis. He was almost as devastating

while the Wildcats were beating Illinois, 53 to 6, scoring twice and

completing

four of six passes to boost his Conference record total to 158

successes

in 334 throws for 2,163 yards. And for an appropriate conclusion

to his career he ran onto the field at game's end, clad in civilian

clothes,

grabbed the ball over which the teams were fighting, and ran off with

it.

He also ran off with the Chicago Tribune silver football award

as

the most valuable player in the Conference.

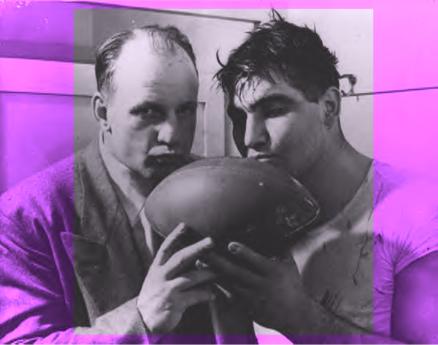

Above:

at Dyche Stadium, Otto prepares to run in for NU's only score vs.

Michigan,

1943.

Below:

Graham receives the conference's MVP award from-- of all people-- Amos

Alonzo Stagg, the legendary University of Chicago coach. [Estate of Otto Graham]

Above:

at Dyche Stadium, Otto prepares to run in for NU's only score vs.

Michigan,

1943.

Below:

Graham receives the conference's MVP award from-- of all people-- Amos

Alonzo Stagg, the legendary University of Chicago coach. [Estate of Otto Graham]

1945: Sweet Sioux Trophy Begins

1945: Sweet Sioux Trophy Begins

NU's last remaining trophy game was the annual Sweet Sioux game against

Illinois.

For a while NU and Illinois had played for an old fire bell;

however,

that trophy was forgotten by the mid forties, and an effort was made by

the

newspapers of the two schools to renew a trophy rivalry.

The following passage is from Northwestern's yearbook, The Syllabus,

and

it describes the 1945 inauguration of Sweet Sioux. Its author is

unknown.

NU

Takes Sweet Sioux

A

tradition was born at the 1945 Northwestern - Illinois football game.

It's

the Wooden Indian, Sweet Sioux, custody of which went for the first

time

to Northwestern by virtue of a 13-7 gridiron conquest of the Fighting

Illini

in Dyche Stadium on November 24. Sweet Sioux, like his colleague

trophies,

the Old Oaken Bucket and Little Brown Jug, will be presented annually,

to

the winner of the NU - U of I cross-state grid match.

The country-wide campaign to transform NU and the U of I into

traditional

pigskin rivals was conceived by Tom Koch, sports editor of the Daily

Northwestern.

Jim Aldrich, news editor of the Daily; Alice Methudy, editorial

chairman

of the Daily; and other staff members threw in their lot, and the hunt

for

a hemlock Hopi was on. Bob Doherty, sports editor of the Daily

Illini,

handled the campaign on the Illinois campus.

After examining all the entries, members of the student Wooden Indian

Committee

selected the brave uncovered by Bill Brown, Northwestern journalism

sophomore.

The Northwestern chapter of Acacia Fraternity donated the redskin.

Unwilling to continue calling the trophy Chief Whosis, the Daily

Northwestern

and Daily Illini conducted contests to name it. Entries poured

in,

and a staff of experts, consisting of Chicago sports editors and campus

athletic

authorities had to be called in to select a winner.

The trophy is one of the few remaining cigar store relics. He was

carved

by hand in 1833 and had a colorful career on his own before being

adopted

by the two universities. Brown discovered the chief in an

Evanston

antique shop, staring quietly at his sixth generation of Americans.

And so Northwestern and Illinois become traditional football rivals,

bound

together by Sweet Sioux. The rivalry is a natural one, and will

undoubtedly

become one of the nation's hottest in years to come.

Well, dear old Sweet Sioux found that it would set up

light-housekeeping

in Patten for the ensuing year when it saw the 'Cats sweep over

Illinois,

13-7.

Hap Murphey was the "man of the hour" for NU rooters as he racked up

153

yards gained in 30 rushes, half of Northwestern's total. Besides

that

record-shattering performance, Hap accounted for the winning touchdown

in

the last quarter.

The Illini, despite their crippled and degenerate state, scored first.

They

took over on the NU 41 after the officials called a chipping penalty on

the

'Cats while an Illini punt was in the air. Jack Pierce swept over

his

own left tackle on the first play and went all the way for a score.

A 79-yard drive gave the 'Cats the tying marker halfway in the second

quarter.

Murphey and Ed Parsegian were the king-pins, Parsegian scoring

and

Jim Farrar knotting the count 7-7.

Bob Jones, sub Illinois tackle, was called on to try a 28-yard field

goal

from a difficult angle in the third quarter. However, his kick

missed

by the thickness of a coat of paint as the ball grazed the upright and

fell

back into the playing field.

NU got the clincher on a 55-yard drive into the promised land.

Murphy

and Ted Kemp did yeoman-like jobs in the attack with Hap doing the

final

scoring of the year.

The

original Sweet Sioux only lasted one year. In 1946 the statue was

stolen

from its case at NU's Patten Gym, and the two schools replaced the trophy with a

tomahawk

in 1947. The statue was recovered soon after, but the

universities

agreed to keep the tomahawk as the trophy, since it would be easier to

transport.

Acacia,

the fraternity which had originally discovered Sweet Sioux, reclaimed

the statue. The statue remained in the fraternity house until a

1985 fire. It is believed that the Sweet Sioux statue was a

victim of that fire.

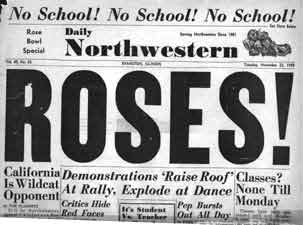

1948:

NU Smells Roses

1948:

NU Smells Roses

NU, under Bob

Voigts, compiled a 7-2 record in 1948 and earned a trip to the 1949

Rose

Bowl. Forty years later, Jesse Wheeler described the game

as part

of an NU Athletic Department retrospective. Wheeler's

article appears

below:

What

you are about

to witness is an event of magnificent proportion, intense historical

significance

and heretofore unprecedented popularity. After a journey of more

than 2,000 miles, you now sit in the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, CA.

Ninety-three

thousand frenzied fans accompany you in singing the last bars of the

National

Anthem. The kickoff of the 1949 Rose Bowl is finally here.

Will Northwestern pull through?

Upon

receipt of

the Rose Bowl invitation following the 1948 season, Northwestern

experienced

wild celebration, the likes of which were considered foreign to its

campus.

Classes were canceled, friendly rioting broke out in the streets, and

traffic

in Evanston and the Loop in downtown Chicago was brought to a halt due

to parading. Thousands of students and alumni formed a caravan of

Wildcat support, traveling to California, certain that this year

belonged

to their team.

The

contest between

the Wildcats of Northwestern and the Golden Bears of California was

made

even more dramatic by the peculiar relationship of the opposing

coaches.

Lynn "Pappy" Waldorf of the Golden Bears had been head coach at

Northwestern

for 12 years before moving on to Berkeley in 1947. His successor

at NU, Bob Voigts, had been an All-America tackle on Waldorf's 1938

Wildcat

squad. Was it possible for the upstart pupil to outsmart his own

mentor?

Alex

Sarkisian,

center for the 'Cats and captain of the 1948 team, recalls, "Bob had a

lot of respect for Pappy. Everyone did. We learned a great

deal from him... he was what a coach should be."

Midsummer

experts

took one look at Northwestern's 1948 schedule and called it

suicide.

The 'Cats, who had finished eighth in the Western Conference the

previous

season, would be facing such powerhouses as UCLA, Michigan, Notre Dame,

and Minnesota. Undaunted, the 'Cats threw themselves upon

their

prey and finished the regular season with a 7-2 mark, outscoring their

opponents 171-77 and posting three shutouts. The unbeaten Golden

Bears were just as impressive in their 10 conquests, outscoring their

victims

276-80. Did the Wildcats feel they had a chance to win?

"We

sure did,"

said Sarkisian, "and we had to feel that way. Otherwise there's

no

way we could have made it from our own 12-yard line to their end zone

with

only two and a half minutes left!"

The

crowd anticipated

a thriller and was not disappointed. Northwestern's senior

halfback,

Frank Aschenbrenner ignited the fireworks early in the first quarter

when

he raced 73 yards for a touchdown, a run which stood for years as the

longest

run from scrimmage in Rose Bowl history. Jim Farrar's

point-after

kick was successful, and the Purple and White went up 7-0. On the

very next play from scrimmage, California All-America fullback Jackie

Jensen

scampered 65 yards for a touchdown, and the Bears knotted the game at

7-7.

In

the second

quarter, Wildcat fullback Art Murakowski plunged over the goal line,

fumbling

in the air. The officials ruled the play a touchdown, and after a

missed extra point, NU led 13-7, a score which held into the second

half.

In

the third period,

Cal's Jensen left the game with a back injury, and it seemed as though

Northwestern had the upper hand. However, Jensen's understudy,

Frank

Brunk, proved just as destructive, and spearheaded a drive that put the

Bears ahead, 14-13.

After

a series

of thwarted drives, the Wildcats took over at their own 12-yard line

with

less than three minutes remaining in the game. Several short

gains

moved NU to the California 43-yard line, setting the stage for perhaps

the greatest play in Wildcat gridiron history-- and certainly the most

dramatic. Ed Tunnicliff, NU's 155-pound halfback, took a direct

pass

from the center, Sarkisian, bypassing the quarterback. As the

California

defense was maneuvered out of position, Tunnicliff, aided by several

down-field

blocks, swept into the end zone for the winning score.

"I

knew they had

that play," Walforf said following the game. "We practiced it

when

I was coach there... it's just that we never used it!"

With

time running

out, NU defensive back Loran "Pee Wee" Day doused the Bears' final hope

as he intercepted a desperation pass at midfield to preserve the

Wildcat

win. Minutes after the game ended, Wildcat fans tore down the

goal

posts, determined never to forget Northwestern's "Rags to Roses"

victory.

Here is another account of the Rose Bowl

Championship.

The following description comes from Northwestern

University: Celebrating

150 Years, by Jay Pridmore. Pridmore's book was

released by the University

as part of its Sesquicentennial

By

Jay Pridmore

It

wasn't that Northwestern was unfamiliar with gridiron glory. It

had

been helping national powerhouses like Notre Dame and Michigan achieve

it

for years. But the 1948 season was different. That year the

Wildcats

finally got their bid to the biggest football game in the nation at the

time

-- the Rose Bowl.

When the Wildcats beat Illinois in the last game of the regular season,

they

clinched second place in the Big Nine. (Without the University of

Chicago,

which dropped football in 1939, and Michigan State, which was admitted

in

1949, it was not then "Big Ten.") Since the conference champion

normally

went to the Rose Bowl but was not permitted to go two years in a row,

repeat

champs Michigan stayed home, and Northwestern got its first chance

against

the best of the Pacific Conference on New Year's Day 1949.

When the bid came, the campus was on cloud nine. A 24-hour

celebration

erupted, with undergrads prowling the streets and fraternity men

serenading

women in their dorms. President Snyder, always bookish and

disciplined,

also got a visit from happy songsters, who tacked a "no school" sign on

his

door. The Admiral even seemed to enjoy it.

On Monday a good-natured "strike" was called. Pledge classes were

assigned

to barricade the doors of classrooms, which was unnecessary, because no

one

went to class anyway. That night a Rose Bowl dance was followed

with

an announcement by Captain Alex "Sarkie" Sarkisian '49 that school was

off

the rest of the week.

NU

Archives

NU

Archives

Such a vacation from academic work seemed extreme to

some, including students

at the University of Chicago, who rushed out with a Daily

Northwestern parody. The Daily Country Club

had the headline "Onions!" mocking the Daily's "Roses!" And

it

purported to quote President Frank "Blissful" Snyder: "Other schools

might

suspend classes for a big thing like a bid to the Onion Bowl, but here

at

CCU (Country Club University), where we have no classes of importance

anyway,

we are not faced with that problem."

Hyde Park's jealousy aside, Coach Bob Voigt's tough Wildcat team was

the

real thing, led by Sarkisian at center and a front line that included

tackle

Steve Sawle '50, the following year's captain. Art Murakowski '51

and

Frank Aschenbrenner '49 did most of the running chores. Everyone

was

ready on January 1, 1949, when the Purple team went up against the

Golden

Bears of the University of California, headed by former Northwestern

coach

"Pappy" Waldorf. The game went down to the final minute, when

Northwestern's

halfback, Ed Tunnicliff '50, scored on a 45-yard end sweep. The

20-14

victory was sealed when Loran "Pee Wee" Day '50 intercepted a pass to

stall

Cal's final drive.

It was a good thing for Evanston that the victory took place in

Pasadena,

or Evanston might have collapsed under another celebration.

Instead,

Cheyenne, Wyoming, bore the brunt of Northwestern's school spirit.

That's

where the "Wildcat Special" Rose Bowl train was stranded for three days

in

a blinding Rocky Mountain blizzard. The streets of Cheyenne were

subjected

to three days of spontaneous Northwestern cheers before 275 students

finally

left town.

1900-1950: What NU's Sports Pioneers Remembered

1900-1950: What NU's Sports Pioneers Remembered

The

following

installment is from

The

Tale of the Wildcats, a Centennial History

of Northwestern University Athletics, a 1951 classic by Walter

Paulison.

Long out of print,

Tale of the Wildcats gives an 'official' history

of NU football, including the following recollections by some of NU's

greatest

players.

These quotes were

collected in 1950 during interviews with some of the oldest surviving

players,

as well as contemporary Wildcats. The players recounted what

were,

for them, the greatest and most remarkable moments on the field.

Raymond Lamke,

class of 1913: "A 65 yard run against Indiana in the rain in

1910.

Score: NU 5, Indiana 0."

Roy

Young, '12:

"It makes you feel good to have your children read about you in the

year

books and to have them think you could do something in your younger

days,

now that you're fat and 50."

James

Solheim,

'27: "When I called for a drop kick from the 42 yard line, one yard

from

the sidelines in the Notre Dame game of '24 and [Ralph] Moon Baker

booted

it between the uprights. Moon was nice about such things. I'd

call

a dumb play and he'd get me out of it with a long run or a great kick."

Leland

Lewis,

'28: "The Iowa game of '26. With that victory NU won [a] Big Ten

championship."

James

Paterson,

'23: "Playing Iowa's conference champions and suddenly realizing that

even

champions aren't superhuman. We ran all over the field in the

second

half."

James Oates, 1893: "Winning

the first

game Northwestern ever played against Michigan in 1892 and taking 13

men

to Minneapolis for the Minnesota game of the same year. We played

60 minute football then."

Don Heap, '38: "Scoring the

winning

touchdown against Notre Dame in '35 and the following year committing

blunders

which lost the game, emphasizing how little difference there is between

the hero and the heel."

Walter Dill Scott, 1895:

"Our defeat

by Michigan, 72-6, in '93."

Albert Potter, 1897:

"Playing every

minute of every game for two years. It was a case of necessity.

We

had few subs."

Harry Allen, 1904: "The

small squads

and the mass plays. To leave a game was a disgrace unless the

player

had to be carried off the field."

Charles Ward, 1903: "When I

backed

up the line against Michigan's 'point-a-minute team' and the great

Willie

Heston nearly knocked my head off."

Charles Blair, '05: "Oddly

enough our

worst defeats are longest remembered. Coach Wally McCornack's

saying

that '60 minutes to play and all your life to think about it' is 100

percent

true."

Albert Weinberger, '06:

"Only in later

life does one come to appreciate the full benefits of football:

how

to accept victory and defeat in good grace; a willingness to sacrifice

and not let your fellow players down."

Robert Wienecke, '25: "The

spirit of

the '24 team which carried to superb heights against Chicago and Notre

Dame and earned Northwestern the nickname of Wildcats."

Jack Riley, '32: "The

battles of wit

and strength against brilliant opponents; the feeling of confidence

engendered

by such teammates as Baker, Manske, Marvil, Bruder, Moore, Rentner, and

others; the satisfaction of having taken part in a winning combination."

Harry Wells, '13: "Those

games in which

it was obvious that team play and team morale were on such a plane that

the team refused to be beaten. That is the greatest contribution

which the game has to offer and the thing for which we should all

strive."

Jack Heuss, '34: "When the

traffic

cop wouldn't let our bus driver make a left turn on Michigan Avenue on

our way to Soldier Field for the Stanford game and thinking what the

50,000

people in the stands would do if we didn't get to the field."

Bill Ivy, '46: "I received

a cut on

my face in the Ohio State game and told Carl Erickson to let me stay in

the game as I was a physician. 'You may be a doctor,' retorted

Carl,

'but I'm the trainer and I'll let you know when you can play."

Alex Sarkisian, '49: "After

the Rose

Bowl victory the photographers asked Coach Voigts to pose with me

holding

the football used in the game. I was still in my wet, soiled

uniform

and I told the coach not to put his arm around me as it would soil his

suit. He looked at me and said, 'I can always get a new suit but

I'll never get another football team like this one.' It was

a privilege to have played under such a fine gentleman and truly great

coach."

1962:

Myers to Flatley

1962:

Myers to Flatley

This was a featured

article from NU's athletic department, written by Greg Jayne in

1987.

Jayne's "Wildcat Legends" article gives an account of the 1962

NU squad,

which for two weeks was ranked the #1 team in the nation.

The 1962 Wildcats,

respected but unranked by pre-season pollsters, started the year with

six

straight victories and spent two weeks ranked No. 1 in the nation.

NU was coming

off a 4-5 season that included a 2-4 Big Ten record and gave no hint of

the greatness to come. But unsuspecting opponents quickly learned that

head coach Ara Parseghian had designed one of the nations most

explosive

offensive attacks, built around the strong arm of quarterback Tom Myers

and the soft hands of flanker Paul Flatley.

It was Myers who

provided the Wildcats with the element of surprise. Freshmen were not

allowed

to compete at the varsity level, so opponents had little idea before

the

season that the 6-0, 180-pound sophomore was one of the nations best

passers.

It didn't take

them long to find out. Myers completed 20 of 24 passes for 275 yards to

lead NU to a 37-20 victory over South Carolina in the season opener.

After just one

game, Myers had established himself among the greatest passers in

Northwestern

history and the Wildcats had served notice that they would compete for

the conference crown.

"Yesterday, a

sophomore quarterback playing his first collegiate game had fans

whispering

his name in the same breath with (Otto) Graham's,” Roy Damer of the Chicago

Tribune reported.

But things were

just beginning for Myers and the Wildcats. In their next outing, they

thumped

arch-rival Illinois, 45-0, and Myers received more rave reviews.

“Myers was a

sharpshooter at finding his targets and a whirling dervish at avoiding

charging tacklers,” Howard Barry of the Tribune wrote.

While some people

were convinced the Wildcats were for real, critics remained. After all,

the best record Parseghian had produced in his six years at the school

was a 6-3 mark in 1959.

But the third

game of the season convinced almost everybody. NU traveled to

Minneapolis

to face the Golden Gophers of Minnesota. The Gophers were defending

Rose

Bowl champions and had won the national title in 1960.

“The answer is

yes, Tom Myers, 19-year-old Northwestern sophomore quarterback, IS that

good,” Barry wrote after the Wildcats had earned a 34-22

come-from-behind

victory. Myers completed 16 of 25 passes for 251 yards and four

touchdowns.

With its third

straight win, NU bolted into the Top 10. More importantly, the Wildcats

had a 2-0 conference mark and were tied for first in their bid to

return

to the Rose Bowl for the first time since the 1948 season.

But Northwestern

was facing its toughest test yet: the Ohio State Buckeyes in Columbus.

The Buckeyes were defending Big Ten champions and had been named

national

champions in 1961 by the Football Writers’ Association. Ohio State

coach

Woody Hayes, in his 12th season at the school, already had achieved

legend

status and had won three national titles.

The Buckeyes began

1962 ranked No. 1, but had fallen from that spot after a loss at UCLA.

Despite the blemished record, OSU still was favored to win the

conference

crown, and surely would put the upstart Wildcats in their place.

But Myers and

company had something else in mind. They marched into Ohio Stadium and

beat the Buckeyes, 18-14, before a stadium-record crowd of 84,376.

Myers

was 18 of 30 for 177 yards. Ten of the completions went to Flatley,

giving

him 29 in just four games.

The victory was

NU’s first in Columbus since 1943, and touched off a campus celebration

that enthusiastic students carried to the streets of downtown Evanston.

“Scent of Roses

Fills Air in Evanston as N.U. Students Roar Welcome to ‘Cats,” read a

headline

in the next day's Tribune. The win had Wildcat fans thinking

"Rose

Bowl" and jumped the team to the No. 2 spot in the national polls.

Notre Dame was

next on the agenda for the Wildcats, and NU took advantage of the weak

Irish to score an easy 35-6 win. The non-conference win didn't surprise

anybody or help Northwestern’s quest for the Rose Bowl berth, but it

vaulted

NU into No. 1 spot in the nation for the first time since 1936.

The Wildcats almost

found fame to be fleeting the next week. Despite outgaining Indiana 504

to 245 in total offense, NU squeaked out a 26-21 win to hand the

Hoosiers

their 17th consecutive Big Ten defeat. The victory wasn't impressive,

but

it was enough for the Wildcats to retain their top ranking and set up

the

biggest showdown of the Big Ten season.

The following

week, NU’s dreams of an undefeated season and a national championship

were

shattered by Wisconsin. The Badgers used a potent passing combination

of

their own, Ron VanderKelen to Pat Richter, and a stifling defense to

register

a 37-6 victory.

The loss dropped

Northwestern into a tie with Wisconsin and Minnesota for first place in

the conference. But the Wildcats had a disadvantage in the race for the

Big Ten title: they were scheduled to play six conference games while

Wisconsin

and Minnesota had seven.

But the schedule

inequity proved to be meaningless as Northwestern took itself out of

the

race the next week with a 31-7 loss to Michigan State.

"Michigan State's

strong, aggressive line and its fast, elusive backs yesterday delivered

the final hammer blows to Northwestern’s hopes for a distinguished Big

Ten campaign." Barry wrote in the Tribune.

The loss also

dashed all NU hopes for a bowl bid. Until 1975, Big Ten teams could not

go to bowls other than the Rose Bowl, a rule that kept the Wildcats out

of post-season play.

NU rebounded in

the final game of the season to beat Miami of Florida, 29-7. The 7-2

record

was the school's finest since 1948.

Although they

didn't make it to the Rose Bowl and they didn't win the national

championship,

the 1962 Wildcats can say something that no other Northwestern football

team of the past 50 years can say:

“We were ranked

No. 1 in the nation.”

Flatley

makes an improbable catch vs. the Irish

NU

Archives

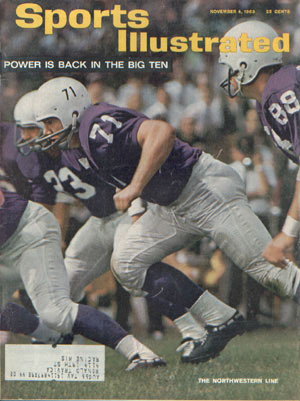

1963:

Sports Illustrated Covers NU

1963:

Sports Illustrated Covers NU

In

1962, Ara Parseghian's Wildcats briefly held the top of the national

football

rankings. The following fall Sports Illustrated published (in the

November

4, 1963 issue) an article about the Big Ten's linemen, and featured the

still-strong

Wildcats on its cover. It was the first time NU football appeared

on

SI's cover, and it would be the Purple's only appearance until Darnell

Autry

burst onto the cover in 1995. Forty years after it was published,

here

is the text from the Sports Illustrated Big Ten piece which relates to

NU:

....The

man in the Big Ten who is perhaps most preoccupied with linemen is

Northwestern's

Ara Parseghian, who has more trouble getting them than anyone else.

Lack

of depth goes with Parseghian and Northwestern, the only privately

endowed

school in the conference, like wind goes with Chicago's streets.

Worse

still, every time it appears that Parseghian has done something to

solve

his problem, Northwestern's line cracks in the middle, and late season

opponents

run through it as merrily as ducklings in an animated cartoon.

Parseghian thought all might be different this year. Although he

does

not get the marginal recruits who go to the state-supported schools, he

came

up with some fine line prospects to go with the passing of slender Tom

Myers.

Even injuries, primarily to Guards Cvercko and Larry Zeno, which

cut

down the strength of his interior, had not dimmed his hopes as he

approached

last week's game against Michigan State with four victories and only a

10-9

loss behind him.

A Late Fader

Unfortunately, when a gorgeous, cloudless day greeted 51,013 for

Northwestern's

homecoming at Evanston, the results for Parseghian were sadly the same

as

in the past. Northwestern got off to a 7-0 lead, but in the

second

half the Wildcat line was torn open for one bolting 87-yard run by

Michigan

State's Sherman Lewis. At the end the Spartans' Duffy Daugherty

celebrated

the announcement of a new five-year coaching contract with a 15-17

victory.

Facing a variety of storming defenses, including a safety blitz that

Northwestern

could not pick up quickly enough, Tom Myers had one of his worst days.

He

completed only nine of 26 passes and had two intercepted. He was

thrown

for 61 yards in losses by the swarming Spartan rushers. Some of

Myers'

slowness in avoiding the rush had him throwing badly off balance. . . .

"I know you don't hear it said that a passing team doesn't play the

real

tough defense," said Parseghian. "But we played well. Lewis

was

the difference. He's been the difference against a lot of people.

We

don't think of ourselves as a passing team. We like balance.

But

you do what you can do best. What are we going to do with Myers?

Make

him a split T runner?"

Northwestern is not the only Big Ten team that passes. The

conference

average is about 20 throws per game. But there is a paradox.

They

are making fewer points. As Illinois, Ohio State and Michigan

State

moved into a tie with 2-0-1 records, each was averaging a fraction more

than

two touchdowns a game.

"I guess they're scoring less because of the tougher defenses," says

Parseghian.

"But the season's only half over. I think you'll see some

scoring."

Northwestern is now, at a very early date, almost out of the

championship

race after being the favorite. While most Big Ten people believe

that

Northwestern will never win a championship because it cannot recruit

enough

of the quality interior linemen it needs to last through the rugged

season,

Parseghian refuses to agree. "I've seen some good line play for

us

this year," he said. "Certainly if we had Cvercko, people would

see

a great one. But we have two or three players who have a chance

to

be really good. Kids like Cerne, Szczecko and Mike Schwager.

We've

been close to a championship two or three times, but have lost out late

in

the season. Because injuries have hurt us, we got hit early.

In

the past five years it was our schedule that got us. For example,

in

that time, the first six teams we've played each year have won 48% of

their

games, and the last three have won 68%."

Doc Urich, Northwestern's end coach, probably put it better than anyone

else

when he said, "About the best we can hope for is that every three or

four

years we can get a group that can make a good run, like some of those

others

do all the time. And we'll need some luck."

It took NU over thirty

years, but it finally proved "most Big Ten people" wrong by winning

three

championships in the span of six years. Critical to those

conference titles,

especially the ones claimed in the nineties, was the Wildcats' superior

line

play.

After this issue of Sports Illustrated hit the stands, Ara Parseghian

would

coach the Wildcats in only two more games, ending with a Northwestern

victory

over Ohio State in Columbus. Parseghian then left for Notre Dame.

1971:

The Wildcats Beat OSU

1971:

The Wildcats Beat OSU

The

following

column, describing Northwestern's last win against the Ohio State

Buckeyes,

was written by The Daily Northwestern staff writer Brian

Hamilton

and appeared in the October 23, 1998 Gameday edition prior to

the

'98 OSU game.

Recalling a '71 shocker

THE LEGENDARY WOODY

HAYES ROAMED THE BUCKEYES

SIDELINE DURING NU'S LAST WIN VS. OSU, AND IT WASN'T BY COINCIDENCE

--by Brian

Hamilton: Gameday

Staff

Woody

Hayes swallowed losses like teaspoons of castor oil. He coached

28

years at Ohio State, about 27 longer than those who dealt with him

would've

preferred, amassing 205 victories and spewing at least that many

expletives

at the officials each game. Once, as an opposing player dashed

unimpeded

toward the end zone, Hayes leapt out from the sideline and tackled

him.

Ohio State faithful wondered why the player got in coach Hayes' way.

Greg

Strunk didn't see who was on his tail, at least not until he got the

film.

On a November day that would make Robert Frost swoon, Northwestern had

just surrendered a touchdown to vaunted Ohio State and Strunk, a

Wildcat

cornerback, received the ensuing kickoff.

Ever

hear 80,000 hosannas suddenly cease? If you're curious, look Greg

Strunk up. He's listed in Phoenix, and he's got the original

America's

Funniest Home Video stashed away. Down a touchdown and a ton of

confidence,

Strunk cradled the kick and started to his right. He hugged the

sideline

all the way, for 93 yards, and the only guy close to him was a graying,

irascible ball of Buckeye fury named Woody, chugging ever so hard, but

failing to record his first career tackle this day.

"I've

got the film of it," Strunk says. "Woody Hayes was running down

the

sidelines after me, throwing his hat. It did get a lot quieter

after

that."

If

there were two things that wouldn't happen under Woody Hayes' watch in

Columbus, both of them were losing to NU at home. Hayes might

have

had his players put their hand on the playbook and swear as much.

But for one Saturday in 1971, NU got Woody, a 14-10 win special only

because

it hasn't happened again since. Which makes keepsakes like Jerry

Brown's something of a collector's item. Sitting unobtrusively in

his home, still there to this day, is the game ball each and every

Ohio-native

NU player received after the shocker. Brown is now [1998]

NU's co-defensive coordinator, but what he'd get most defensive about

in

1971 was the smack his high school buddies laid on thick and heavy

during

summers back home.

Three

of Brown's teammates from Roosevelt High in Kent, Ohio, went to Ohio

State.

Brown received a polite "Thanks but no thanks" from Hayes and the

parting

gift of a scholarship to NU. For two years, the Buckeyes got the

better of the 'Cats. Brown got the worst of the trash talk.

"Each

summer we'd get together and talk, and they had two on me, so I owed

them

one," Brown says. "They always throw it at me now that they beat

me two out of three, but I always say, 'Isn't it the last one that

counts?"

[ed. note: Notre Dame fans, in particular, should pay attention to

that

last quote...]

From

practices that week in '71, you'd think this was the only one

that

counted. Countries mobilize for war with less intensity than NU

displayed

before the Ohio State game. NU was 5-4 heading in, but it might

as

well have been 5-400, as long as it was Woody Hayes and Ohio

State.

With 24 players from the Buckeye State on the roster, the term "light

practice"

meant one in which only smaller bones were broken.

Larry

Lilja probably hates Ohio State more than anyone, if only because the

assorted

nicks from that week haven't healed yet. Lilja, now NU's strength

and conditioning coach, was a freshman tight end in 1971. Since

freshmen

were ineligible to play then by NCAA mandate, Lilja had the envious

task

of mimicking Ohio State's offense on the scout team. He may have

gotten his current job on the merits that he survived the week with

four

limbs intact.

"I

just remember getting the shit beat out of me that week," Lilja

says.

"Players were just so intense. I remember thinking, 'Geez, I hope

they play like this during the game."

Says

Strunk: "Kids from Ohio were in the locker room, standing up and giving

speeches. The coaches realized the magnitude of the game.

They

were really grinding on us. They worked real hard, and they made

us work real hard."

What

Strunk started, fullback Randy Anderson finished with a one-yard dive

in

the fourth quarter, erasing a 10-7 deficit. While the world's

largest

funeral procession ensued outside-- the Buckeye's slim Rose Bowl hopes

were dashed by the loss-- a virtual Mardi Gras flooded the visitors'

locker

room at Ohio Stadium, which was sort of like holding a Fourth of July

bash

at Buckingham Palace.

For

all the scarlet and gray in the stands, the prevalent colors on the

field

were black and blue. "You could hear the hitting," Strunk says.

Although

the game soundtrack featured more snaps, crackles and pops than a bowl

of Rice Krispies, the visitors' lockers got the worst. Anything

that

made a loud noise when punched would suffice. Of course, after

beating

Ohio State on ground more sacred than Jerusalem, it was clearly

necessary

roughness.

"To

be able to do that in front of their fans was a big thrill," says Barry

Pearson, the leading receiver for that NU squad, who had three catches

on the day. "The guys from Ohio were really going nuts, because

they

could go home and hold their heads up. I guess it just means so

much

to get that one, you could just lose all the others as long as you got

that one."

|

|

|