1906:

Varsity Football Vanishes

1906:

Varsity Football Vanishes

Another

section from The

Tale of the Wildcats, a Centennial History of

Northwestern

University Athletics, by Walter Paulison. Tale of

the Wildcats gave an 'official' history of

NU football and its milestones, including the temporary end of NU's

intercollegiate

football program:

A

storm of criticism

followed the 1905 season. The brutality and danger of football

and

the overemphasis placed upon the game were viewed with alarm in many

quarters.

A nationwide survey by The Chicago Tribune showed 18 deaths

[but

none at NU] during the year from injuries.

In the midst of all

this clamor against

football, Northwestern University, along with Columbia and Union

College

in the East, took the drastic action of abolishing football.

Northwestern's

action is summed up in the following extract from the report of a

special

committee, headed by Dean Thomas F. Holgate, to consider the athletic

situation

of the University: 'After full consideration of the place accorded to

athletic

contests in educational institutions at the present time, and in

particular

to intercollegiate football contests, and with full knowledge of the

efforts

recently made to eliminate the evils from such intercollegiate

contests,

your committee is of the opinion that the wisest course for the

University.

. . is to discontinue all intercollegiate football contests for a

considerable

period of time, if not permanently; and it accordingly recommends

that from and after Commencement Day, June 21, 1906, all

intercollegiate

football contests be discontinued for a period of five years.'

The Board of

Trustees adopted the report

and intercollegiate football vanished from the campus. Louis

Gillesby,

director of physical education at the Evanston Y.M.C.A. was appointed

Athletic

Director. He instituted a program of inter-class football.

In his annual report... in 1906-07, President Harris said, 'Fully four

times as many students as under the old system have taken the regular

exercises

and competed in vigorous games.'

In order to correct

the abuses that

had developed in the conduct of intercollegiate football, the [Big Ten]

Conference adopted a set of regulations at a special meeting, March 10,

1906. These reforms included the following provisions: one year

of

residence was necessary for eligibility; only three years of

competition

were permitted, with no graduate student eligible; the season was

limited

to five games; no training table or training quarters were permitted;

student

and faculty tickets were not to cost over fifty cents; coaches were to

be appointed only by University bodies and at moderate salaries; steps

were to be taken to reduce receipts and expenses of athletic contests.

At the same time,

the football rules

committee modified the game by adopting new rules which included the

following

provisions: playing time of each half was shortened to 30 minutes, six

men were required on the line of scrimmage, one forward pass was

allowed

to each scrimmage, hurdling was forbidden, and the neutral zone was

established.

The 'reform' rules

established by the

Conference encountered much criticism, especially those concerning the

three-year limit and the training table. The Conference stuck by

its guns, however, and insisted that there must be full observance if a

school wished to retain full membership. Michigan bitterly

opposed

a number of the rules and withdrew from the Conference, not to return

until

1917.

1908:

Football Returns to NU

1908:

Football Returns to NU

An

installment

from

The

Tale of the Wildcats, a Centennial History of

Northwestern

University Athletics by Walter Paulison. Here Paulison

describes

the return of varsity football to campus in 1908, after a two-year

absence:

.

. . Northwestern

students and alumni were none too happy about the abolition of

intercollegiate

football [in 1906]. Although the inter-class games resulted in

more

men playing the game than formerly, the feeling gradually developed

that

the system of home football could not be maintained without the

interest

and inspiration of some intercollegiate competition. During the

fall

of 1907, a widespread demand for the return of intercollegiate football

was made by both students and alumni. In December a petition

signed

by nearly 90 percent of the student body was presented to the Board of

Trustees asking permission to play three intercollegiate games during

the

1908 season.

In a report to the

Board of Trustees

reviewing the football situation at the University, President Harris

pointed

out that 'the request of the students deserved respectful

consideration;

first, because of the very remarkable way in which the students had

shown

themselves loyal to the action of 1905. It is not possible to say

too much for their self-control and public spirit. Second, the

high

character of the student body was assurance that the game, if allowed,

would be conducted on a high moral plane. Third, it deserved

consideration

because the principle of democracy, which is vital to the development

of

the right college spirit, demands that no part of the University, the

trustees,

the faculty, or the students, shall disregard the desires of any other

part, or unnecessarily override them. This request was very dear

to the students, and it was felt their wishes ought to be

followed

unless there are better reasons to the contrary.'

. . . It was finally

agreed that the

football reforms instituted by the rules committee and the Conference

had

been effective and that the reasons for abolishing the game as an

intercollegiate

sport had been remedied. As a result, the Trustees agreed to

grant

the petition with the provision 'that the alumni be asked to make up a

guarantee fund of $1,000 to cover any possible deficit.'

And so, after a

two-year moratorium,

intercollegiate football returned to Northwestern in 1908.

Restoration

of the game did not mean that the University was able to field a team

that

in any way equaled the fine 1905 squad. Coach McCornack had left

to enter the practice of law in Chicago, most of the players with

varsity

experience had graduated, and, more important, many rule changes had

been

made in the game, including the introduction of the forward pass.

Indeed, it was to take years before Northwestern recovered from the

effects

of the two-year layoff from football.

1911:

The First Homecoming

1911:

The First Homecoming

From

The

Tale

of the Wildcats, a Centennial History of Northwestern University

Athletics

by Walter Paulison.

Alumni

had made

a practice of returning for a football celebration for a number of

years

before 1911, but it was not until that fall that the event was

officially

labeled 'Homecoming.' The Daily Northwestern announced

the

affair as follows:

For the first time

in its history Northwestern is to have a

Homecoming

Day--

one on which all the "old grads" can

get together

and

have a good time. . . .

According

to

the Daily, 'elaborate preparations are underway to make this

the

big day of the season, and in addition it is hoped that this will

become

an annual event.'

These

hopes were

realized, for during the succeeding years Homecoming grew into

a

stupendous affair with elaborate torchlight parades, lavish decorations

of fraternity and sorority houses, and huge pep rallies and bonfires on

Long Field.

Compared to these

latter-day celebrations,

the first Homecoming was tame indeed, but it was a start, and it can't

be said that the affair was taken half-heartedly. The

Alumni

Association appropriated funds to cover expenses; the Evanston

Commercial

Association passed a resolution to decorate business places; the

Athletic

Department reserved choice seats for alumni at the football game with

Chicago,

and President A.W. Harris sent a letter to alumni urging them to attend.

In urging a big

turnout for the Friday

night parade and rally, The Daily Northwestern said:

Bring your tin pans, lard buckets, whistles,

noisy-phones,

racket makers,

muskets-- anything and

everything that

looks or

listens LOUD and come along to

the big

pandemonium

tonight . . . forget your

books, forget

the board bill,

forget everything but

that you are alive.

. . . . A crowd of

7,500, many of whom

were 'old grads,' attended the game and saw Stagg's Maroons defeat the

Purple, 9 to 3.

The following year

an inspired Purple

eleven gave the Homecoming celebrants something to cheer about by

upsetting

Illinois, 6-0. After the game, students and alumni formed a snake

dance that wound its way to Fountain Square for an impromptu

celebration.

A student circus

with fraternity and

sorority acts was one of the highlights of the 1915 Homecoming, while

in

1917 a near riot prevailed as the Homecoming crowd celebrated a victory

over Michigan. In 1919 a spectacular pep rally and reunion day

was

held in honor of the termination of World War I.

These early

Homecoming celebrations

set a pattern which has been adhered to in recent years. The only

break occurred during World War II, when the parade and house

decorations

were discontinued for a three-year period. They were resumed in

1946

on a grander scale than ever before. Over 50 floats were in the

line

of march and the house decorations bordered on the colossal.

1915:

Paddy Driscoll:

NU's First Star

1915:

Paddy Driscoll:

NU's First Star

This installment

was a featured article from NU's athletic department. The

uncredited

column, written to commemorate Paddy Driscoll's 1974 induction into the

National Football Foundation Hall of Fame, gives an account of

Driscol,

Northwestern's phenom 90 years ago.

"He started

it all." -- Waldo Fisher, retired Northwestern associate athletic

director.

Those

words were

spoken about a legend, a memory, and most important, a tradition.

They describe Northwestern's immortal John Leo "Paddy" Driscoll.

During

a career

full of successes which most only dream about, Paddy won recognition as

an All-American and election into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

[At the 1974 NU-Purdue game], Paddy was remembered for all of his

successes,

as he was honored for his induction into the National Football Hall of

Fame posthumously.

A

native of Evanston,

Paddy began his career at Evanston High School as a 128 pound

fullback.

After [becoming] a prep legend, he chose to continue his exploits at

Northwestern.

Northwestern

fans

were treated to a preview of his tremendous talents when he returned

the

opening kickoff 95 yards for a touchdown in his first varsity game--

against

Iowa in 1915. From then on, there was little doubt Paddy would

gain

stardom. Driscoll added weight and became a 145 pound triple

threat

All-American at Northwestern. His collegiate coach, W.L. Kennedy,

termed Driscoll "the greatest football player ever produced in the

country."

Paddy

will be

remembered forever as an artist and devotee of the dropkick. He

was

simply sensational. Once he was knocked unconscious, only to

return

and boot a 55 yard field goal, the longest of his career. As a

professional

player, Driscoll still holds the NFL records for the most field goals

dropkicked

during a career (40), the most dropkicked in a game (4), and the

longest

dropkicked field goal (50 yards, on two occasions).

After

World War

I cut short his Northwestern career, he went on to lead Great Lakes to

a 17-0 Rose Bowl triumph. He teamed up with George Halas on a

touchdown

pass, and averaged 47 yards on six punts in the game.

In

1921, Paddy

became player-coach for the Chicago Cardinals, where he established all

his professional dropkicking records. A three sport star in

baseball,

basketball, and football in both high school and college, Driscoll

played

infield for the Chicago Cubs baseball team during one summer between

football

seasons. A further example of his athletic versatility was when

he

led St. Mel's prep cagers to a National Interscholastic basketball

title

in 1925.

Paddy

proceeded

to advance in the cage coaching profession, moving to Marquette in 1936

for five years. Then he switched sports again and became an

offensive

backfield coach under former teammate George Halas with the Chicago

Bears

in 1941. When Halas stepped down as head coach in 1956, Driscoll

received the head coach position and immediately directed the Bears to

a 9-2-1 record and the Western Conference Championship. He

remained

with the Bears until his death in 1968.

Driscoll's

NFL Hall of Fame bust

Driscoll's

NFL Hall of Fame bust

1924:

Northwestern Becomes

The Wildcats

1924:

Northwestern Becomes

The Wildcats

The Chicago

Tribune's Wallace Abbey is credited with giving NU's

Purple team the

nickname "Wildcats," after its valiant effort in a close loss to

Chicago.

Below is Abbey's famous quote from the front page of the Tribune,

in the context of the first three paragraphs of his column.

Something more

than ordinary wildcats are required to subdue wildcats gone completely

vicious, entirely aroused, by the temptation of a great prize, a big,

juicy

piece of "meat." Let us call that "meat" the Big Ten football

championship

and consider the following situation at Stagg Field yesterday

afternoon,

to which 32,000 hoarse fans will attest today:

It was the fourth

quarter of the annual Chicago-Northwestern grid battle. Football

players had not come down from Evanston: wildcats would be a name

better

suited to Thistlethwaite's boys.

Baker was there, and he was the chief wildcat giving his supreme effort.

Stagg's boys,

his pride, the eleven that had tied Illinois a week ago, were unable to

score. Once they had been on the 9 yard line and had been stopped

stone dead by a Purple wall of wildcats. The game was fast

waning.

. . .

1925:

The Soldier Field Shocker

1925:

The Soldier Field Shocker

The

following article appeared in the winter 1995 edition of Northwestern's

Alumni News magazine. It was written by George

Beres , a former NU Sports Information Director.

According

to the Alumni News , Beres was told the story of NU's 1925 epic

game against Michigan by the late Tug Wilson, "a key figure in one of

the legendary victories of Northwestern Football history."

Following the Beres article, I have also included

a passage describing the game from Walter Paulison's 1951 book, Tale

of the Wildcats.

The

infamous game at Soldier Field ranks #8 on the HailToPurple.com

list of the 25

greatest games in Northwestern History. It is also on Northwestern's

official list of NU's greatest games from 1882 to 1982.

***

NU and the Mud

Cost

Michigan

the 1925

National

Title

BY

GEORGE BERES

The 20th century still was young as two men stood

hunched together under

the stands of Chicago's Soldier Field, watching the rain fall in

torrents.

It was the morning of November 7, 1925-- 40 years before anyone

thought

of carpeting a football field with water-resistant plastic grass.

On

that day, lightly regarded Northwestern was to play the nation's #1

team,

Michigan, in the lakefront stadium. Never would the weather play

a

more dominant role in deciding the outcome of a football game.

It

had rained most of the week, and the gridiron was a quagmire. As

the two brooding figures watched, sections of the field disappeared

before

their eyes under growing puddles of water. The playing field was

beginning

to resemble choppy Lake Michigan, which churned just beyond the

stadium's

east gates. The shorter of the two men, Michigan coach Fielding

Yost,

wanted nothing to do with it.

"Tug,

I coach a football team, not a swimming team. How can I tell them

to play a game on a field we can hardly see?"

Tug

Wilson was the young Northwestern director of athletics, later

commissioner

of the Big Ten Conference. He told me years later, "I said to

Fielding:

'Look, we've already sold 40,000 tickets to this game. You know

we

can't afford to call it off."

Yost's

Michigan team had outscored its five previous opponents 180 to 0.

But he knew, as Wilson did, that rain was the great equalizer,

the

ally of the underdog. His Wolverines were well on their way to a

national

championship, and he wanted nothing to do with a game neutralized by

the

elements. He stared balefully at the water-logged gridiron and

continued

to plead that the game be postponed. But he knew it was a lost

cause--

that the one thing he couldn't argue with was gate receipts. So

Wilson--

and the budget-- prevailed, and Michigan sloshed out into the mud to do

battle.

Ironically, fewer than 20,000 fans showed up for the game, as

half

of the advance sale ticket holders refused to venture out into the

deluge.

Object

as he might to the weather, Yost was shrewd enough to adapt to it

as best he could. He held pre-game practice on higher ground

north

of the gridiron and dressed his squad in rubber trousers.

Walter

Eckersall, University of Chicago Hall of Famer who refereed the game,

told Wilson afterward: "In my 25 years of football, I never saw worse

conditions.

There were pools of water on the field, and in some places the

players'

feet sank into the field two or three inches."

A

Michigan student manager grabbed a life preserver off a Chicago bridge

and brandished it on the sidelines. The hapless Wolverines could

have

used it. Northwestern took the opening kickoff and was stopped

inside

its 30. The Wildcats immediately established the stalemate

pattern

for the game by punting on first down. Clearly, it was a

liability

to have possession of the ball on your side of midfield.

That

first punt became the game's pivotal point. Michigan's

All-American

quarterback, Benny Friedman, fumbled the ball, and Northwestern

recovered

deep in Wolverine territory. Three attempts into the line gained

nothing.

Then Wildcat fullback, Tiny Lewis, moved back to the Wolverine 18

to

try a drop-kicked field goal. The kick had just enough distance

to

get over the crossbar, barely missing one of the uprights. For

the

first time in six games, Michigan had been scored upon!

The

field goal, coming on the first series of the game, was with a

comparatively

dry ball. Soon the ball became waterlogged, making it even harder

to

handle and further neutralizing the offenses. The supply of balls

was

limited. Eckersall was able to put new ones into play only twice:

at

the start of the third and fourth quarters. For the rest of the

game,

nature dictated identical game plans for both teams: make two attempts

to

gain, then punt on third down. When two plays failed to gain a

first

down (there was only one in the game), it became routine for Eckersall

to

call time so he could wipe the ball for the anticipated third down punt.

After

Friedman's early disaster, neither team risked fielding a punt.

There

was no danger of the ball rolling. When it landed, it stopped

dead

in the mud. The game's only first down came when Michigan back

Bill

Hernstein slipped and slid for a gain of 11 yards. Conditions

deprived

Michigan of its potent pass weapon, Friedman to Bennie Oosterbaan.

Only

one pass was thrown, and it fell incomplete.

The

Wolverines refused to panic. Their willingness to play a waiting

game looked as if it would pay off late in the third quarter.

Northwestern

had used three plays in a a desperate but unsuccessful attempt to move

the

ball beyond its own 10.

Then

came the play that haunted Yost the rest of his career. Instead

of punting on fourth down, Wildcat captain Tim Lowry had Lewis down the

ball

in the end zone for a safety, giving Michigan two points.

The

rules of the day gave Northwestern the ball again with first down on

its own 30. When Lewis eventually punted on third down, his kick

carried

well into Michigan territory. Neither team threatened again.

Rain

kept the remaining action near midfield, and Northwestern floated away

with

a stunning 3 to 2 victory.

Michigan

still went on to win the Big Ten crown. But the loss in the

rain washed away its chances for the mythical national championship.

Yost

took little comfort from the fact that on the same day his team was

wallowing

in the mud, similar conditions existed throughout the Midwest.

The

weather was so bad 160 miles to the south in Champaign that the great

Red

Grange of Illinois came up with negative rushing yardage against

Chicago.

At

national rules meetings after the season, Yost demanded and got a

revision

of the safety rule that Northwestern had exploited against Michigan.

The

new rule required the team that suffers the safety to give up the ball,

kicking

to its opponent from the 20-yard line.

But

the legislation came too late to retrieve the 1925 national title Yost

always insisted he deserved-- the title Michigan left buried in the mud

of

Soldier Field.

From

Tale of the Wildcats, by Walter Paulison:

[The

game] was against Michigan, the site was Soldier Field, and the weather

was so miserable that postponement was seriously considered. More

than

75,000 persons had purchased tickets, but so bad was the day that only

about

40,000 were in the stands at the kickoff [yes, this is double what

Tug

Wilson claimed in the article posted above. Apparently no one was

overly

concerned with getting accurate attendance numbers during the monsoon].

The field was deep in mud and standing water, and rain continued

to pour down throughout the game.

Shortly

after the opening kickoff Benny Friedman fumbled a punt [return],

and Barney Matthews recovered for Northwestern on the Michigan

five-yard

line. Lewis was stopped at the line in two attempts [or maybe

three; who knows?], so stepped back and kicked a field goal.

Thereafter

the game developed into a kicking duel, as proper ball handling was

almost impossible. In the fourth quarter [or maybe late in the

third...

] Michigan marched to the 10-yard line before the Wildcats dug in and

held

for downs. A gale was blowing directly in the faces of the

Northwestern

players, so it was decided to take a deliberate safety rather than run

the

risk of a blocked punt. The ball was snapped back to Lewis, who

fell

on it back of the goal line for a safety. A few minutes later the

game

ended with Northwestern ahead by the strange score of 3 to 2.

"That

safety," says Capt. Lowry, "was a joint decision made by quarterback

Bill Christmann and myself. I don't know why he never received

more

credit, as I think he always played a heads-up game."

NU

and Michigan slog through the first quarter in Soldier Field.

NU

and Michigan slog through the first quarter in Soldier Field.

Photo NU Archives

1935:

Waldorf's Irish Killers

The next two

installments

are from Pappy: The Gentle Bear, by Steve Cameron and

John

Greenburg. Pappy tells the story of Lynn "Pappy" Waldorf,

Northwestern's longest-serving and most winning coach. The book

focuses

on Waldorf's tenure at Cal, but gives some wonderful insight into his

time

at NU as well (Greenburg lives in Evanston and has written extensively

about NU's 1949 Rose Bowl). The book is in print.

NU had won the

Big Ten title in 1930 and '31, but by the time Pappy arrived-- prior to

the '35 season-- the 'Cats had slumped. Waldorf decided to focus

on the Notre Dame game. One week before the NU-ND matchup, the

undefeated

Irish had beaten Ohio State in the first "Game of the Century."

When Waldorf

assessed his first Northwestern team, he decided that the players were

decent, but not overwhelming. So he dusted off a strategy he

learned

form Zuppke.

'I'll always

remember his advice,' Waldorf said. 'He told me, "When you're

faced

with one of those years when your material is only fair and you're not

going to win many games, put your eggs in one basket. Pick a

tough

team and lay for it. Knock it off, and you've got yourself a

season."

'That's exactly

what I did my first year at Northwestern. The target I chose was

Notre Dame.'

. . . . Waldorf

stressed that playing on a college football team was only part of the

total

educational experience a university offers, and players were at school

primarily to get an education. In addition, he told them his door

was always open. He invited players to discuss their courses with

him and he saw to it there were no conflicts between practices and

classes.

His players were allowed to miss practices or games if their studies

required

it.

. . . . When

Northwestern hosted Purdue in the first night football game in Big Ten

history, the Boilermakers took a 7-0 lead by returning a punt for a

touchdown.

Following the kickoff, the Wildcats marched down to Purdue's 2-yard

line.

With first and goal to go, the ball was snapped to sophomore fullback

Fred

Vanzo, who fumbled just as he was about to score. Purdue

recovered

and went on to win by that same 7-0 margin.

The target showdown

came on November 9, and it set up perfectly for Waldorf, since Notre

Dame

was coming off a stunning 18-13 upset of a supposedly unbeatable Ohio

State

juggernaut. . . Notre Dame boasted passing and punting sensation

William Shakespeare - yes, a direct descendant of the English

playwright.

This chain of

events set up one of the most literary match ups in college football:

Shakespeare

against Northwestern end Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. . . . As the

grueling

afternoon wore on, the Northwestern defense continued to befuddle Notre

Dame's attack. As for Longfellow, Henry made two huge plays as

Northwestern

scored a 14-7 upset in a game which propelled Waldorf to national Coach

of the Year honors.

[After the game,

line coach Burt Ingwersen found Waldorf worried about the next game,

rather

than celebrating the victory] 'Aw, Lynn,' drawled Burt, 'You should be

kickin' up your heels. . . Remember when they took us to that nightclub

a few months ago and all those guys started dancin' with the

hostesses?

You just sat there nursin' a drink and that ol' boy kept callin' you an

ol' pappy. How'd you like it if we started callin' you

"Pappy"?'

And the name

stuck.

As one of the

rewards for the national coaching honor, Waldorf's picture appeared on

boxes of Wheaties. 'Unfortunately, General Mills didn't send me

any

cash. Instead, they sent cases of that breakfast food to our

house,'

Waldorf said. 'I got tired of eating Wheaties, Louise got tired

of

eating Wheaties, our two daughters got tired of eating Wheaties, and

even

our dog Pixie got tired of eating Wheaties.'

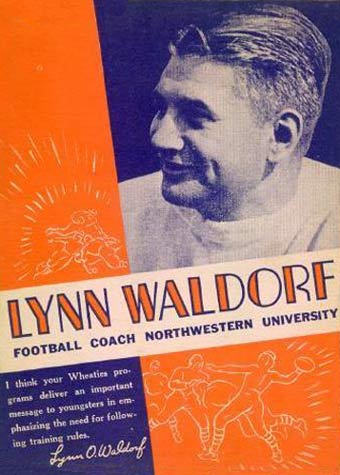

The book's

authors did not

include it, but the GoUPurple research

team dug it

up: above, a

copy of the Pappy Waldorf

Wheaties box

from 1935.

The book's

authors did not

include it, but the GoUPurple research

team dug it

up: above, a

copy of the Pappy Waldorf

Wheaties box

from 1935.

1936:

a Season of Dominance

We conclude our

quote from Pappy: The Gentle Bear with an account

of

the Ohio State and Minnesota games during the 1936 season, which

provided

NU

with its fifth Big Ten title.

In the fourth

quarter of their game with Ohio State, Northwestern lined up in a

formation

no one had ever seen before-- an unbalanced line with two tackles and

the

quarterback just to the right of the center, left end Johnny Kovatch

standing

a yard off the line of scrimmage in a wing position and right half Don

Geyer a yard off the line in a gap between the right tackle and right

end.

Waldorf called it 'The Cockeyed Formation,' but in fact, it became

football's

first slot formation and it gave tailback Heap four targets in the days

when most teams sent out only two receivers.

Heap connected

with Kovatch on a 42-yard gainer. Three plays later, Heap scored

from five yards out and Northwestern had scrambled to a 14-13 victory.

. . . That cardiac comeback injected NU with the confidence they

needed to take on Minnesota, which had used the infamous "buck lateral"

move to score four touchdowns in its previous two games.

Halloween afternoon,

1936, was Northwestern's first home sellout in six years, and Pappy had

a trick planned for the Gophers-- yet another defensive wrinkle in

which

a tackle would not charge from the line of scrimmage. This was

the

first attempt at a 'read and react' defense, and it also involved

elements

of what now is known as the zone blitz.

Minnesota came

to Evanston with a 28-game unbeaten streak, and hundreds of sports

writers

from coast to coast were present to chronicle the momentous

collision.

In addition, there were nine radio hookups, including the CBS and NBC

national

networks.

On Minnesota's

second play, Andy Uram broke loose on the buck lateral as Northwestern

blew its special coverage. Uram should have scored, but he

slipped

on the rain-soaked field and went out of bounds at the Wildcat 23-yard

line. Ultimately, the Gophers got nothing when a fake field goal

went awry and the game stayed scoreless at halftime. . . .

Years later,

Pappy described the final minutes of that game, saying, 'There were

five

minutes to go, Minnesota had the ball on their 20-yard line and called

for an off-tackle play. Uram came off tackle. Vanzo, who

had

been in all 55 minutes, was in at the right side to tackle him.

Just

as he was tackling Uram, he flipped the ball to (Rudy) Gmitro, their

fastest

man. Gmitro, in the 100-yard dash, could beat Vanzo by 10 yards.

'Our films showed

that, as Vanzo was coming up on his knees after making the hit on Uram,

Gmitro was six yards down the field, and yet 40 yards further down the

field, just as Gmitro dodged our safety and had a clear field for a

touchdown,

it was Vanzo who caught him from behind. How he got there, I will

never know.

'After 55 minutes

of awfully hard football, as hard as any boy ever played, he had the

courage

to get up and go after what seemed to be the impossible, and it saved

the

game for us.'

Despite the Gophers'

remarkable rushing statistics on a muddy track of 256 yards on 36

carries,

an average of 7.1 yards per rush, they had been shut out. Their

four-year

unbeaten streak had come to an end.

1936:

a Season of Dominance, Part Two

1936:

a Season of Dominance, Part Two

The current installment

was a featured article from NU's athletic department. Written in

1986, the article is not credited, but Frank J. Mack and Charles

Loebbaka

were contributing writers for the department during that autumn.

The department's account of the 1936 Wisconsin game, given below in its

entirety, provides a nice continuation of the previous passage, which

focused

on Pappy Walforf and the beginning of the 1936 season.

It was Saturday,

the day of the Wisconsin game. Just last Monday, Northwestern

students

had celebrated a 6-0 victory over Minnesota by striking classes to

dance

and prance about campus in a euphoric stupor.

And now, the Badgers

were in town, about to provide the Wildcats with a form-fitting glass

slipper

to cap a cinderella story.

A perfect fit;

NU took a 26-18 victory in front of more than 30,000 fans at Dyche

Stadium

and with that the Cats brought home their first (and last) undisputed

conference

title [Ed. note: not much

optimism exuded here-- clearly

NU's staff in '86 were still in the midst of the Dark Ages].

Northwestern entered

the season minus eight lettermen, four of which had started the

previous

year. They were regarded in the media as a second division team,

and victories over Ohio State and Minnesota were considered major

upsets.

After [Wisconsin

and NU] traded punts, Northwestern, known as a safe, steady and

consistent

team, struck first when halfback Don Heap of Evanston returned a punt

32

yards to the Badger 28. After a Badger offsides penalty, Heap

kept

the Cats rolling when he found an opening and dashed 15 yards to the

nine-yard

line. After a running play gained two, NU went back to Heap, who

tore through the line for the touchdown. The extra point made it

7-0.

But that's when

the Wisconsin passing game introduced itself to the Evanston

crowd.

Right halfback Clarence Tommerson did most of the damage on the

day.

After the NU score, he drove the Badgers from their own 33 to the

Wildcat

19 before a penalty and a sack pushed them back and forced a punt.

The Wisconsin

defense held on the ensuing series, and Tommerson and Company were back

on the go. The 6-2 halfback marched his squad from its own 28 to

the score. Roy Bellin highlighted the charge with a 35-yard run

around

end, and he finished it when he caught a pass in the endzone from

Tommerson.

The extra point was no good and NU held the lead, 7-6.

The Wildcats answered

Tommerson's challenge with a 67-yard scoring drive. Fred Vanzo

returned

the kickoff 15 yards to the NU 33, where it was fullback Steve Toth's

turn

to cut up the Wisconsin defense. After he and Ollie Adelman

combined

combined for a first down, Adelman connected with Toth to the Wisconsin

38. Four running plays moved the Cats down to the 15, and then

Toth

sprinted through a gaping hole, eluded the Badger safety and scored

standing

up. Toth kicked the extra point for a 14-6 lead, and that's how

the

half ended.

The Wildcats almost

broke things open just before intermission when Adelman fielded a punt

at his own 15 and ran 85 yards into the endzone. The play was

called

back, though, because Adelman's knee was on the ground when he fielded

the punt.

While the first

half was nothing to yawn about, the action in the second half provided

"some of the flashiest football seen here for some time," as The

Daily

Northwestern put it.

The Wildcats widened

their lead just four plays into the period. Heap received the

kickoff,

broke several tackles and went 77 yards before being brought down at

the

Wisconsin 18. After two runs up the middle gained no yardage,

John

Kovatch took an end around in for the score. The extra point was

blocked for a 20-6 NU lead.

Wisconsin, not

to be outdone, worked double time for its second score. Starting

at their own 45, the Badgers moved to the seven-yard line on the seven

plays. Bellin scored on a sweep on the next play, but the

touchdown

was called back because of an offsides penalty. Tommerson brought

Wisconsin back to the five, and on third and goal, he ran it in.

The extra point was missed and NU led, 20-12.

The Wildcats put

their title on ice on NU's next possession. After the kickoff,

Northwestern

powered its way to another score without throwing the ball once.

Heap, Toth and halfback Bernard Jefferson carried the load, and Toth

finally

barreled his way in from three yards out. His extra point attempt

was wide and NU was up 26-12.

Wisconsin tallied

once more behind its passing attack. The Badgers started at their

own 18 and completed six passes en route to the score with three

minutes

left in the game. The final toss went from Howie Weiss to Vernon

Peake for seven yards. The extra point was no good.

But the clock

struck midnight on the Badgers' upset bid. For the year-long

underdog

Cats, though, the bell never tolled. Though NU had to face

Michigan

the following week (Northwestern won 9-0 for a perfect 6-0 conference

mark),

the victory over Wisconsin clinched the title. It also sparked

another

celebration on the Evanston campus, as an official day without classes

was scheduled for the end of the season.