|

|

|

NU's Chaotic

1918 Season

Posted

3/24/20

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Northwestern's Chaotic

1918 Season

By Larry LaTourette

The

1918 H1N1 flu pandemic actually began in late 1917 and inflicted its

first wave of deaths in early 1918, but the disease’s greatest wave

shook the United States in October and November 1918. Unlike the 2020

Covid-19 pandemic, which has resulted (as of March 24) in a third of

the world engaged in a systematic lockdown and partial quarantine, the

quarantines in 1918 were sporadic. Evanston and Chicago dipped in and

out of quarantine seemingly week by week. That fall, Northwestern’s

upcoming football season had already been heavily modified by World War

I: the school was slated to play a full Big Ten schedule, but the war

demands eventually required NU to push its October game with Ohio State

to November, because the War Department began to limit travel.

Initially, the team moved its November game with Chicago to October,

since the teams were local.

In the first decades of the Twentieth Century, NU employed students

from both campuses, Evanston and Chicago, for its varsity football

teams. However, the War Department, which had taken over all college

campuses, had also restricted preseason practices for football, and

this limited the Chicago players’ ability to practice with the team. To

make up for this, Northwestern head coach Fred Murphy, starting his

fifth and final season leading the Purple, split the team into two

squads and had the Chicago players practice on a field at 26th Street.

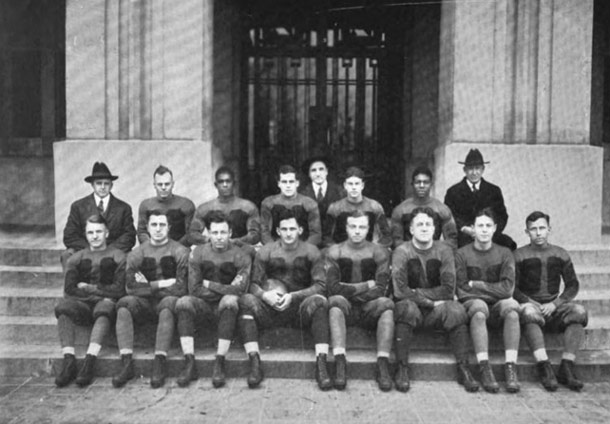

The Evanston-based portion of the 1918 team. Coach Murphy is top left.

The Evanston-based portion of the 1918 team. Coach Murphy is top left.

Even with the two-squad system, Northwestern’s preparation for the

coming season was further disrupted by the war. All football players

were sworn into reserve military service, and the team’s lounge in the

NU gymnasium was taken over by campus military authorities. The flu

pandemic finally made its presence felt when assistant coach Jack

Ulrich (top row, center, in the photo above) fell ill.

An out-of-conference game with Knox College, intended to kick off the

season at Northwestern Field on October 12, had to be postponed when

Evanston suddenly came under flu quarantine. The quarantine also threw

a game with Michigan State in doubt. By mid-October, the flu crisis was

affecting college football more than the war adjustments. While some

high school and college games were played with full-capacity stands,

others were being canceled due to spreading quarantines. By October 19,

the Purple team’s camp was put in quarantine and all players were given

shots. Games with both Michigan State and Michigan were canceled: the

state of Michigan was under a flu emergency. The game with Ohio State

was moved to early November.

As NU continued to scrap its October college games, it decided to add two games with nearby military training camps.

Great Lakes, which had also canceled a game with a team from Michigan,

hosted NU at its training facility just north of Evanston on October

26. Health inspectors decided that the game was relatively safe, and

the teams staged the game free of charge to spectators. Thousands of

naval trainees packed the stands to watch. Great Lakes was supposed to

have traveled to Pittsburgh earlier in the month for a game with Pitt,

but that match was also canceled because of the dire flu situation in

Pennsylvania. Football great Walter Camp had recently visited Great

Lakes to lend support to its team and rally the trainees. The game with

NU was mostly notable because Great Lakes’ team featured Northwestern

legend Paddy Driscoll, who had joined the Navy after leaving NU. The

Bluejackets were heavy favorites, but Northwestern held the servicemen

to a 0-0 tie in muddy conditions. The spectators seemed unconcerned

with the pandemic that weekend; most of the nation was riveted to news

coming from the Argonne-Meuse front in France, where German forces were

trying to bring in reinforcements after being mauled by Allied attacks.

The weekend also brought the end of America’s first-ever national

daylight savings time period that summer and fall.

Instead of playing a huge game against Michigan the following week, NU

attempted to host Ohio State for its delayed game with the Buckeyes.

However, Chicago announced that the city would be in quarantine the

weekend of November 2. While Evanston had lifted its quarantine, the

city’s health department was worried about such a big game at

Northwestern Field. NU still held classes, but nearly everything else

was gone: the university’s chapel was closed, as were Evanston’s public

schools, churches, and theaters. Coach Murphy pressed hard for the

game, and—somewhat surprisingly—the city board of health sided with the

coach, deciding that the flu risk was safe enough in Evanston to hold

the game.

With less than 48 hours to go before kickoff, however, word came that

the Buckeye team was being stopped by Ohio health authorities. NU

scrambled the day before the game and arranged for Municipal Pier Naval

Reserve to play at Northwestern Field. Despite the health threat and

the last-minute change, about 2,000 fans came to Evanston to see

Municipal Pier rip apart NU, 25-0. The Naval Reservists had already

defeated Illinois and Chicago during the season.

Given the chaos of scheduling during the season, Murphy and NU had no

idea what team they might be able to play next. They still had a big

game against Chicago on the schedule, now slated for November 16, but

no team left for November 9. A trip to Lincoln, Nebraska, at the end of

Nobember was now in question. Murphy did, however, want to keep NU’s

scheduled game at Iowa, at all costs.

Murphy drilled the team during the week, even though it had no opponent

for Saturday. Again, the team found an opponent at the last possible

minute. The Purple rescheduled its delayed game with Knox College for

November 9 at Northwestern Field. By this time, however, the flu was

raging, and NU had lost many players to illness, injury, and military

call-ups. Murphy, desperate to keep his roster filled, took in several

NU Medical School students who had had a little undergraduate football

experience.

The Knox game, scheduled quickly, with flu worries swirling around the

north Chicago suburbs, and with restricted attendance, drew only 300

spectators. To this day, it is the lowest-attended Northwestern home

game during the entire time that NU has played football on Central

Street, beginning in 1905. Knox scored a touchdown in the first minute

of the game on a 90-yard run, but Northwestern quickly overwhelmed the

local college, staging a 47-7 rout.

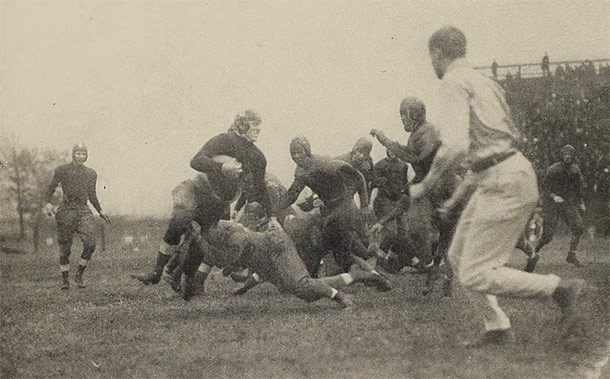

The Purple battling Knox in front of just 300 fans at Northwestern Field.

The Purple battling Knox in front of just 300 fans at Northwestern Field.

The team’s preparation for the homecoming game against Chicago was

disrupted—not by flu, but by victory celebrations as the war came to an

end. Practices were suspended as players joined in victory parties. The

war had put a huge burden on NU: nearly all male students were signed

up in the reserves, and even the Daily Northwestern had suspended

operation—in its place was the Northwestern Weekly, a newspaper

exclusively written and published by female students. The students

noted that some of Northwestern’s oldest traditions had fallen to the

wayside in the wake of the war and the pandemic. “Once upon a time

there were some college traditions,” a columnist wrote in the Weekly

Northwestern, “but they were all shot to pieces. . . You need have no

fear of wearing the wrong kind of hat. We aren’t giving a hang about

such things, just now.” As news of the armistice broke, Northwestern

students streamed from their dorms, screaming, singing, and dancing in

the quads. The students built an enormous bonfire on Davis Street, and

the party continued for an entire day.

The Evanston – Chicago area was out of quarantine, and Northwestern

even staged a football prep rally on Tuesday, attended by 1,700

students who cheered for the team and for the end of the World War. To

mark the ends of both quarantine and the war, Evanston decked out in

both Northwestern and American colors. Evanston storefronts put purple

banners in their windows, and NU decorated the football field with red,

white, and blue colors. The school expected at least 10,000 fans.

However, the area fans and alumni were still wracked by the effects of

the pandemic, and there was still a lot of concern about large

gatherings. Bad weather that moved in early in the day didn’t help

attendance, either, which was just under 6,000. The fans who did brave

illness and the weather got to see NU whip its rival, 21-6.

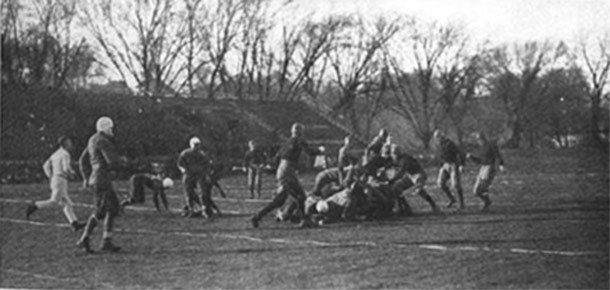

NU and Chicago play in front of stands less than half full.

NU and Chicago play in front of stands less than half full.

The Purple made their only trip out of state in 1918 for their last

game of the season, against Iowa. Nebraska should have been NU’s final

opponent the following week, but one last schedule change nixed the

game. NU chose not to conduct two road games straight, while Nebraska

substituted Camp Dodge for the game.

NU’s team was rag-tag by the end of the year, and med school subs took

an increasing share of responsibility for the team. Iowa, however, was

relatively healthy, and the Hawkeyes handled NU easily in a 23-7 win.

It knocked Northwestern out of a possible second-place finish in the

Big Ten, and it ended a wild, chaotic, and unpredictable season.

All photos are from the 1920 Syllabus.

|

|

|