|

|

|

|

|

By GoUPurple

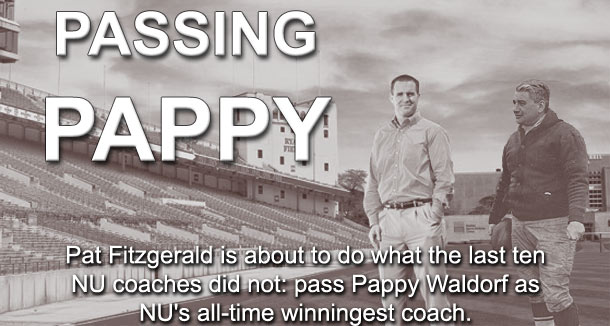

As

his seventh season as head coach of the Wildcats concludes, Pat

Fitzgerald stands at the threshold of winning more games at

Northwestern than any coach before him. When he wins his fiftieth

game, either with a long-sought January 1 bowl victory or a

non-conference win early next season, he will pass Lynn “Pappy” Waldorf

for the record. Doing so, Fitzgerald will break one final streak

of frustration, bad luck and heartbreak that remains from

Northwestern’s football challenges in recent decades: Fitzgerald will

have stayed at NU long enough to have passed Pappy, long enough to have

contributed to a stable and enduring football program with a

long-tenured coach. Great coaches have appeared in Evanston

between the terms of these two men—Voigts, Parseghian, Agase, Barnett,

and Walker among them—but none stayed, or could stay, long enough to

make it to 50 victories.

It is not a groundbreaking mark only for Fitzgerald. As we will

see, it is a landmark for the school and the program as well.

PAPPY

The man whom Fitzgerald will pass, Lynn Waldorf, had a successful

coaching career before he came to Northwestern and an even more famous

one after his departure from Evanston. Like Fitzgerald,

Waldorf was a two-time All American as a player (for Syracuse), and

like Fitz, Waldorf became a head coach at a very young age.

Waldorf made his head coaching debut in 1925, at age 23, at Oklahoma

City University. He coached there for four seasons, turning

around the fortunes of that small school’s team and earning a

conference championship.

Waldorf entered coaching at the major college level in 1929 at Oklahoma

State. He was a stunning success, powering the Cowboys to three

Missouri Valley Conference championships during his five seasons in

Stillwater. From there, Pappy made a one-season stop at

Kansas State, coaching the other Wildcats to a Big Eight Conference

title.

Noting Waldorf’s reputation as an up and coming coach, NU athletic

director Tug Wilson began to work to replace Northwestern’s coach, Dick

Hanley, with Waldorf. Hanley had coached the ‘Cats to

back-to-back Big Ten titles in 1930 and ’31, but his team was in a

brief slump, and Hanley had lost support of the NU

administration.

Even during this period in Northwestern’s football history, a period

festooned with conference titles and near misses at national titles, a

problem was beginning to crop up between the football head coach and

the school’s administration and athletic director. At a school

with such recruiting, admissions, and academic restrictions as

Northwestern, it can become very difficult to achieve and maintain a

balance between providing its football coach with the support he needs,

jeopardizing the school standards, or undercutting support for its

coach—through negligence, indifference, or even hostility. With

Hanley, it had become a hostile withdrawal of support. And so,

after eight seasons, NU’s winningest coach, the only coach to date with

multiple Big Ten titles, was essentially forced out, and Waldorf was in.

Pappy prowls the sideline in California [HTP Photo Archive]

Waldorf, as he had in each of his previous schools, struck immediate

gold. During his first season he led the ‘Cats to a seismic upset

of Notre Dame, in South Bend, just one week after the Irish had beaten

Ohio State in the original “game of the century.” The game is

famous for a twist that Waldorf, along with assistant coach Litz

Rusness, developed: the shifting defense. Before the ’35

game with the Irish, most defenses lined up in the same formation the

entire game. Instead, Waldorf’s ‘Cats paid attention to the

offensive formation, then shifted from a 5-3 formation into a formation

more suitable to defend the offense as set. The result was a 14-7

upending of the Irish. The win allowed Waldorf to claim the very

first national coach of the year award at the end of the ’35 season.

The following year NU would lose to Notre Dame, which might seem a bit

of a letdown, until one realizes that the 1936 NU – Notre Dame game was

to determine the national championship. Northwestern, in Pappy’s

second season, had beaten Minnesota, snapping the Gophers’ 28-game

unbeaten streak and earning itself the #1 national ranking in the AP

Poll’s first year. The ‘Cats would lose out on the national

championship (which Minnesota would ultimately claim, though it did not

win its own conference), but would win the unshared Big Ten title.

Waldorf was winning games, and he was doing so by bringing in top

flight talent, including Bob Voigts and Bernie Jefferson (both of whom

had key roles in the ’36 title season), Bill DeCorrevont (the national

#1 recruiting pick and to this day NU’s top-rated recruit), and of

course halfback Otto Graham.

Graham had come to NU on a basketball scholarship and was a music

major; his place on the Dyche Stadium grass was supposed to be as a

French horn player for NUMB. However, Graham was also a skilled

baseball player and a versatile football player, and during his

freshman year he guided his fraternity’s intramural football team to

the IM championship. Waldorf watched, and he made his move,

recruiting Graham for the Wildcat football team.

Pappy’s observation paid off. Graham’s 1941 football debut

was a stunner. He helped to dismantle Waldorf’s old school,

Kansas State, 51 to 3 in the season opener. Graham was set to

begin a three-year campaign to tear apart the Big Ten’s passing records

en route to All American honors and a place as one of NU’s greatest

athletes. By 1943 Graham was a commanding figure in the

conference, and Pappy had surpassed Hanley’s win record, taking the

title of the all-time winningest coach at NU.

The following three seasons, however, were somewhat disappointing, and

by the end of the 1946 season, Pappy had become frustrated with the

school and its restrictions. When asked at one point about the

relatively small number of players NU had on its roster compared to

other Big Ten teams, Waldorf had complained, “Overall, things were

uneven at Northwestern. We were never able to offer as much

financial aid as we were allowed to under the rules.”1

When the University of California’s athletic director offered Waldorf

that school’s head coaching position—and a sizable raise—Waldorf

countered by requesting control over his staff and that he would report

to the president of the university2, shaking off the restrictions that

had encumbered him at NU. And so, in early 1947, with 49 wins

after 12 seasons as the Wildcats’ coach, Pappy Waldorf left for Cal.

While head coach of the Bears, Waldorf enjoyed a string of three

straight Pacific Coast Conference titles and three straight Rose Bowl

appearances. The first Rose Bowl for Pappy was, of course, the

1949 Rose Bowl against his former team and his former student,

Northwestern, coached by Bob Voigts.

THE COACHES SINCE PAPPY

Voigts, another very young head coach, resembled Fitzgerald even more

than Pappy did. Voigts was an NU alumnus, who as a Wildcat player

was named All American. He, like Fitz, was 31 years old when he

took the reins at NU. He was a former assistant coach, but had no

experience as a coordinator or head coach.

When Voigts in his second year led the ‘Cats to the famed Rose Bowl win

over Pappy’s Cal Bears, it seemed that Voigts was the perfect fit for

Northwestern. But that fit was not to last. As with Hanley

and Waldorf, Voigts found his team in a rut a few years after stellar

success. And as it had with Hanley, the administration decided to

cut itself free of its coach. Voigts found alumni and

administration support evaporating toward the end of the 1954 season,

and he left, essentially forced out as Hanley had been.

Voigts’s successor, Lou Saban, did not work out, but the next coach,

Ara Parseghian, certainly did. Parseghian rebuilt the team,

recruited top-flight talent, and by 1958 had the Wildcats poised to

make a series of runs at the conference. While NU did not win a

title under Parseghian, it came close several times, and it remained

very competitive. By the end of his eighth season at NU, however,

Parseghian had also become as frustrated as his predecessors.

Northwestern would not

budge on its academic restrictions, which was OK, but it also did not

give its football coach the level of control and resources that other

Big Ten schools afforded their programs. “I’m restive,” Parseghian

famously uttered when asked about his possible plans to leave

Evanston. Eventually, he did, for a school that promised more

resources, and had the tradition to back it up: Notre Dame. The “Era

of Ara” ended after the 1963 season, and Ara had 36 wins and one game

over a .500 record. He would be the last coach to leave Evanston with

a winning record.

One of Parseghian’s

assistants, Alex Agase, took the helm in 1964, struggled for a few

seasons, and then hit gold in 1970, taking the ‘Cats to the brink of a

title and a Rose Bowl bid two years in a row. During his nine seasons,

Agase notched 32 wins. However, he also became unhappy with the

support he had received from the Northwestern administration.

|

|

Ara: the Coach Who Would Be King

[HTP Photo Archive]

|

Agase had even more reason to complain: in 1970 Robert Strotz became

the president of Northwestern, and Strotz was not one to increase money

and resources for athletics. Again, Northwestern had a solid

coach. Again, the coach grew disappointed with the resources

available to his program. And again, he was denied what he needed

to succeed. Agase left for Purdue before the 1973 season.

So began the Dark Ages. Coaches Pont, Venturi, Green, and Peay

had no realistic hope of claiming win #50 at Northwestern. Green,

realizing the futility of hoping for what he needed to succeed at NU,

bolted for Stanford. Pont, who was by 1977 also the athletic

director, removed himself from command after five seasons.

Venturi and Peay were let go. But NU’s next president, Arnold

Weber, was setting the stage for the end of the Dark Ages, and the next

coach would again have a shot at passing Pappy.

Gary Barnett’s first few years at NU and fantastic run through the Big

Ten in 1995 and 1996 put him half way to 50 wins. However,

Barnett often looked for another home, and by 1998 his search had

picked up. Part of this was Barnett’s own wanderlust; however, a

significant reason for Barnett’s resume blizzard was the same old

problem that had plagued the football program for nearly 70

years. Barnett, holder of two Big Ten football titles, NU’s first

since Pappy, was being paid less than incoming basketball coach Kevin

O’Neill. Athletic director Rick Taylor had shown Barnett a

surprising level of disrespect, and when Barnett made a fairly

reasonable plea for more resources, the response was much the same as

it had always been. And so, Barnett took the opportunity to

return to Colorado, after winning 35 games at NU, one shy of Dick

Hanley.

When Taylor announced Randy Walker as Barnett’s successor, the first

piece was in place at having a coach who would stay the distance and

build an enduring program at NU. The second piece was Taylor’s

own replacement four years later. Mark Murphy was a director who

understood the vital importance of keeping his good coaches, and he was

determined to keep Walker, who was at that point three years removed

from the 2000 Big Ten title and had placed the program back on stable

ground. In the spring of 2006, Murphy signed Walker to a contract

extension through 2011. The extension would have meant Walker

would have been at Northwestern for 13 seasons, one longer than

Waldorf. Walker was ecstatic, and the pattern of frustration,

disappointment, and erosion with Northwestern’s football coaching

position was at last at an end. It seemed Walker was destined to

pass Waldorf and surpass 50 wins.

Nothing, sadly, is what it seems. The pattern indeed, had ended,

but it would take the next coach to reach the milestone. The

Wildcat nation lost Walker, but Fitzgerald is just as committed.

Murphy moved on, but his successor has shown an even more passionate

commitment to the program and to its longevity. And so a new

milestone is to be set. And never in our lifetimes will we see

the coach who will eventually pass Fitz.

1-2: Cameron and Greenburg, Pappy, The Gentle Bear, 2000.

Other references: Paulison, The Tale of the Wildcats, 1951.

LaTourette, Northwestern Wildcat Football, 2005.

|

|

|